By Mandi Ross

In the recent DR Distributors, LLC v. 21 Century Smoking, Inc.1 case ruling involving a variety of sanctions against the defendants and their counsel, Illinois District Judge Iain D. Johnston (among many other things in a very long ruling) stated: “The E-Discovery Process: Same As It Ever Was: E-discovery is still discovery. Unquestionably, at times, ESI discovery can be complex. But complex issues were not at play here. The same basic discovery principles that worked for the Flintstones still work for the Jetsons.”

Is Keyword Search “Same As It Ever Was”?

Is what Judge Johnston said really true? Let’s take a look at one of the discovery functions that many lawyers and other legal professionals understand (or at least think they understand): keyword search. Despite the increasing use of Technology Assisted Review (TAR) approaches such as predictive coding, lawyers in many cases still use keyword searches to identify potentially responsive documents to be reviewed for production.

Since most lawyers started out learning how to conduct keyword searches by using Westlaw2 and Lexis3 to conduct searches for case law to understand precedents, this method is comfortable to them. The goal for case law searches (find specific decisions that meet their needs), however, is significantly different from the goal for eDiscovery searches (find documents responsive to the case, which could be thousands or even millions of documents, as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible). Best practices for eDiscovery search require a methodical approach that starts at the core of the case itself: the claims, defenses, and fact pattern that define the language of the who, what, where, and when of the matter.

Prism Litigation Technology’s whitepaper Don’t Stop Believin’: The Staying Power of Search Term Optimization4 outlines Prism’s unique Search Term Optimization process, which centers on five key objectives:

- Issue Analysis: Create an unambiguous definition of each issue that characterizes the claims being made and the defenses being offered.

- Logical Expression Definition: Define the specific expressions that encapsulate each issue. Multiple expressions may be required to convey the full meaning of the issue.

- Component Identification and Expansion: Distill each logical expression into specific components. These components form the basis for the expansion effort, which is the identification of words that convey the same conceptual meaning (synonyms).

- Search Strategies: Determine the appropriate parameters to be used for proximity, as well as developing a strategy for searching non-standard or structured data, such as spreadsheets, non-text, or database files.

- Test Precision and Recall: In tandem with the case team, review small sample sets to refine the logical expression statements to improve precision and recall. The comfort level on precision and recall can vary from case to case, so consider it a dial that can be turned up or down, depending on the needs of the case.

The whitepaper also stated that “[t]his approach has achieved a staggering 80 percent reduction in data volumes.” Pretty good, right? Perhaps. But we can – and must – do better today. Here’s why.

Conducting Discovery Quickly and Proportionally is More Challenging Than Ever

When the Electronic Discovery Reference Model5 was created in 2005, it was designed to provide a framework for conducting discovery where, as you move through the life cycle of the discovery process, the volume of data is reduced while the percentage of relevant data rises. However, according to StatInvestor6, the volume of data created worldwide in 2005 was 0.1 zettabytes (each zettabyte is approximately 1 billion terabytes). By last year, the volume of data created worldwide had risen to 47 zettabytes, which is 470 times more data than 2005. That exponential growth is expected to nearly quadruple by 2025 to 163 zettabytes. This growth is, in part, due to the numerous ESI sources that didn’t even exist back in 2005, such as mobile devices and cloud repositories. With the volume and disparate nature of ESI today, conducting discovery that is proportional to the needs of the case is more challenging than ever. So, it’s no wonder we’re seeing a huge increase in proportionality disputes in cases – at least 889 case rulings involving proportionality disputes just last year, which reflects almost an 87% increase over 20197!

That level of data growth and variety of sources has put a tremendous strain on traditional workflows for eDiscovery, which often involve collecting custodians’ entire data collections (sometimes even through device imaging). To identify, preserve, collect, analyze, and process that level of data to prepare it for search and review can take as much as 28 days or more before search and review can commence. With tight time frames, particularly in courts that utilize so-called “rocket dockets,” that level of delay can make it difficult to meet discovery deadlines.

From Flintstones to Jetsons Utilizing “Index-in-Place” Technology

Unfortunately, Fred Flintstone’s car (powered by Fred’s own feet) is much too slow to get us to our eDiscovery destination on today’s ESI super-highway. How, then, do we trade up to George Jetson’s spaceship? It’s simple: go to the source.

The sheer volume of collecting entire data repositories and moving them forward to processing, review and production makes this method an antiquated process. Instead, why not simply go directly to where the data lives and conduct the search earlier in the EDRM lifecycle? With this new “spaceship” approach, you collect only what is necessary for the matter at hand – a much faster and direct approach to eDiscovery.

Index-in-place technology can help navigate today’s ESI super-highway. By indexing the source data, searches can be conducted in situ, without having to wait for entire data stores to be collected and processed first. That not only streamlines workflows for specific litigation cases, but it also supports:

-

- Reusability to apply similar searches to different cases, swapping out custodians, product names, date ranges, etc.;

-

- Support for data audits;

-

- Proactive monitoring for compliance needs, such as Environment/Social/Government risk (ESG) monitoring;

-

- Investigations into potential corporate intellectual property (IP) theft; and

-

- Defensible disposition of Redundant, Obsolete or Trivial (ROT) data.

X1® provides an Enterprise Platform that enables legal, compliance, and IT teams the ability to identify, analyze, and act on data in place across the organization for litigation, data audit, and compliance initiatives. Index- and search-in-place technology offers unprecedented support for desktops and laptops, in addition to file servers, cloud repositories, and other enterprise data sources. This process addresses a major pain point of traditional eDiscovery preservation and collection methods.

“To best realize the benefits of proportionality, the process needs to be effectuated further upstream, so that you are, for example, running detailed keyword searches and other culling parameters (such as data ranges) in place prior to collection and then only collecting the ESI that is responsive to your specific criteria”, said John Patzakis, Co-Founder and Chief Legal Officer of X1. “This is the functionality X1 delivers with our index-in-place search coupled with targeted collection. The case law and the Federal Rules provide that the duty to preserve only applies to potentially relevant information, but organizations that do not employ the right operational processes typically default to data over-collection, thereby losing the benefits of proportionality.”

With the ability to perform searches within the source data and initiate targeted collections of potentially responsive ESI, the time frame to review is reduced from approximately 28 days down to about 3 days – spaceship speed indeed! That can make or break your ability to meet deadlines for discovery.

What’s the Impact on the Search Term Optimization Process?

While the timing for keyword search is moved much earlier in the process, the workflow for actually conducting and optimizing the search results doesn’t change much. You still need to:

-

- Define the issues associated with each of the claims and defenses;

-

- Define specific expressions that encapsulate each issue;

-

- Distill each logical expression into specific components, expanding as needed to include synonyms;

-

- Determine the appropriate parameters to be used for proximity and non-standard data; and

-

- Sample and test the results for accuracy.

Most importantly, conducting keyword search using this methodical approach earlier in the eDiscovery life cycle results in extensive cost savings by avoiding over-collection and eliminates processing fees. Additionally, because less data is required to be hosted for review and eventual production, review costs (which are by far the most expensive part of eDiscovery) are dramatically reduced. These costs decrease even further when combined with a technology-enabled workflow8 that aligns discovery with the merits of the case by prioritizing custodians and narrowing the scope of discovery early.

Case Study Example of Expedited Search

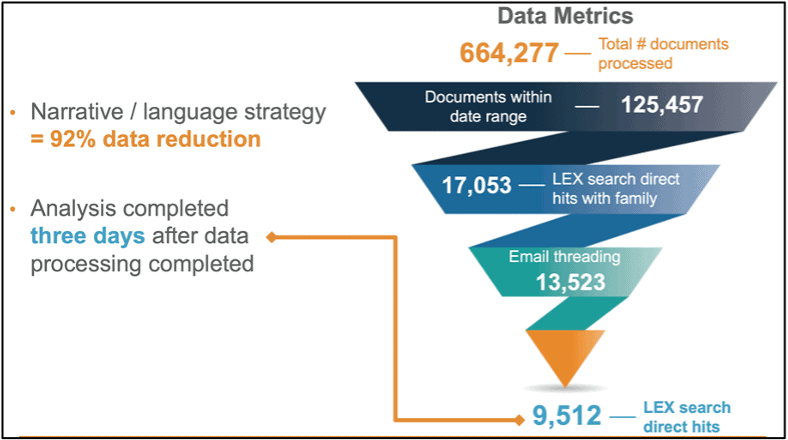

Recently, Prism conducted a search optimization proof of concept in relation to eDiscovery advisory services for a client. Data from five custodians had been collected, resulting in a starting file count of 664,277 files to be considered for discovery. After reducing the population through date range culling and targeted searching, the number of documents with direct search hits was only 9,512, with analysis completed in only three days! Here’s an illustration of how the data population was reduced so quickly:

Figure 1: Case Study Illustrating Application of Search Term Optimization

It is important to note here that had the client used index-in-place technology, Prism’s data experts would have started with only 17,053 documents (the hits that would have occurred by searching the data in place), reducing the time and expense even further by avoiding processing, culling, and storage costs for the larger data set.

Conclusion

So, is keyword search the “same as it ever was”? The thought process is essentially the same, yes, just as transportation from one place to another will eventually get you there regardless of the method. To be efficient in locating relevant documents, managing your budget, and meeting your deadlines, using these new methods is certainly the best choice. If you’re going to be a cartoon character from the Hanna Barbera9 collection, be George Jetson, not Fred Flintstone!

[1] eDiscovery Today has a write-up about the DR Distributors, LLC case here and here.

[2] Westlaw Edge, © Thomson Reuters.

[3] Lexis+, © LexisNexis.

[4] Don’t Stop Believin’: The Staying Power of Search Term Optimization, Prism Litigation Technology © 2019.

[5] Electronic Discovery Reference Model, published by EDRM.

[6] Information created globally 2005-2025, by StatInvestor.

[7] 2020 eDiscovery Case Law Year in Review, available for download here.

[8] Hanna Barbera, © Wikipedia.

Mandi Ross is the CEO of Prism Litigation Technology and Insight Optix.